The Auteur Series: Magic, Myth, and Mutilation

Michael J. Murphy examined through the lens of the auteur theory.

This is the first post in what I believe will become a regular series on the Apple Park Film Club. After last month's post about the auteur theory, I felt it wasn’t fair of me to write a criticism of the theory without presenting my application of it. The last article was the most negative I’ve been on the film club so far and I’ve repeatedly said that’s not what this is about, so I hope to redress the balance.

It would be easy for me to pick an established auteur. Someone well established in the canon of cinema who it would be impossible to refute as an auteur. It would be easy to write yet another article praising the work of P.T. Anderson, Tarantino, and Christopher Nolan. It would be much harder to pick an obscure filmmaker. A filmmaker who never thrived yet produced a vast body of work spanning low-budget horror, thriller, and fantasy cinema.

That filmmaker is Michael J. Murphy.

I have picked Michael J. Murphy for a range of reasons:

I disagree with Studio Binder’s assertion that a director must have a certain level of competence. The ideas and themes in Murphy’s work presented themselves early in his career when he was still learning the ropes.

Murphy was a filmmaker who did what he could with what he had available but always had a clear vision for what he wanted to make.

Murphy was a filmmaker from Portsmouth in the UK. This makes him one of my peers and I have a specific interest in his work.

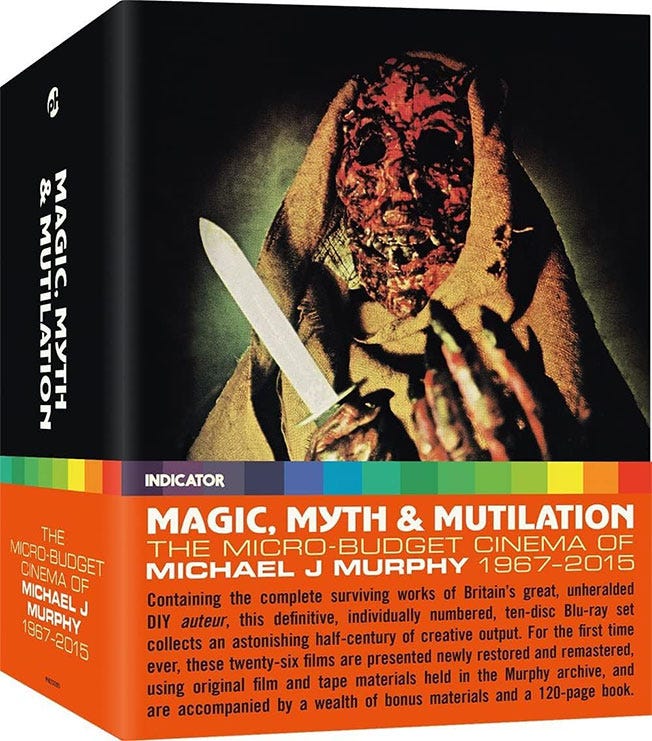

Fortunately, the boutique distributor Powerhouse Films took the time and the patience to restore and release almost all of Murphy’s work. Released in 2023 on their Indicator label, Magic, Myth, and Mutilation contains twenty-six of Murphy’s films (including alternative edits and releases), documentaries, and a collection of essays discussing the man’s work. The existence of this box set is a joy because it proves that even long-thought-lost bodies of work in varying states of disarray can still be made available to the public if someone cares enough.

Before we move on to discussing the work of Michael J. Murphy in any great detail, I must establish my rules for viewing a filmmaker's films through the auteur lens. I’m not arrogant enough to believe I should get to rewrite the rules, but in the last article, I called for rigidity. The best place to start is right here with my analysis. As such, here are the Apple Park Film Club’s rules for the auteur:

Consistent visual style and motifs - this is to replace the instantly recognisable rule used in Backstage. Instantly recognisable implies that one should be able to look at a single frame from a filmmaker’s work and instantly identify the artist behind it. Many filmmakers use the stock in trade shots to tell the story effectively and efficiently, especially on a low budget. Which brings me to the second rule:

Budget doesn’t matter - some believe auteurs can’t operate within the big-budget, Hollywood filmmaking world. This is nonsense, especially when we acknowledge that the original writers at Cahiers used Hitchcock as their prominent example. In a world where Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Christopher Nolan are working in the Hollywood system; the argument that auteurs can’t operate in this space falls apart.

Consistent themes, groups or ideas - This is the real crux of the argument. An auteur uses their films to explore themes, groups, or ideas that appeal to or interest them. It seems too contained to simply say theme. If a filmmaker wants to explore the working class throughout their work across many genres and styles, can we not argue that they are still an auteur? Throughout this and other auteur series articles, I’ll discuss whether or not that filmmaker explores similar themes, groups, or ideas throughout their work.

It’s a simple, yet rigid, set of rules that will allow me a framework to establish whether a filmmaker fits the auteur remit. There will be some flexibility, for example: the filmmaker may not use a consistent visual style and motif in every film. If a director makes films using traditional grip equipment throughout their career and then makes a found footage film, they won’t be penalised by the rules; especially if the films fit thematically with the director’s work.

Michael J. Murphy

Let’s move on to the subject of today’s article: Michael J. Murphy. Murphy was born in Portsmouth in 1951 and started making films as early as fourteen (if not before). His first feature production, The Legend, was completed in 1968 and premiered for a sell-out run in Michael’s home. Financing and promoting the film himself, Michael was able to sell out multiple screenings to friends, family, and people from the city of Portsmouth.

Michael’s headteacher was so impressed with what he saw, that he pulled some strings and secured Michael an internship at Elstree Studios in the UK. Leaping at the opportunity, Michael was left somewhat underwhelmed and disappointed by the experience. At the time, unions had a lot of control over film production in the UK and with Michael not being a union member, it was hard for him to secure a decent position. Instead, he spent most of his time observing established filmmakers, including Stanley Kubrick. When EMI took over Elstree a few years later, Murphy decided to leave Elstree before the new owners got rid of him.

It didn’t take long for Michael to return home in a bid to start his filmmaking powerhouse, eventually named Murlyn Films and run with his close friend Phil Lyndon. Producing films in his home city of Portsmouth or on the sunny Greek islands. Focusing on the fantasy, thriller, and horror genres, Murphy’s early works were largely confined to limited, local screenings at venues prepared to give him a chance. It wasn’t until the explosion of VHS in the 80s that Murphy was given the opportunity to get his work out there.

Murphy’s dogged determination and team of eager collaborators meant he produced thirty-one films on almost shoestring budgets from 1966 until he died in 2015. A body of work that is largely unknown to modern film audiences. What no doubt comes across as amateur efforts by someone who didn’t know what he was doing, should not be held in such low regard. Modern digital filmmaking makes everything seem so easy. You can shoot as many takes as you want, losing nothing but time. You get immediate playback to check whether the take was good. Editing is simply a case of uploading and syncing footage. Gone are the days when you had to hope the lens was in focus, hope the film made it to the lab, hope that everything went well during processing, hope that the developed film came back in good shape, before physically cutting the film yourself. This is the world that Murphy cut his teeth in, working largely by himself, with a non-professional crew. He should be applauded for it.

I have a special affinity for Michael J. Murphy. The fact that he made most of his work in Portsmouth or the surrounding area connects with me. I love watching his films and seeing sites from my past, like in Torment (1990) where our lead character walks over the Cosham train station bridge. I had a real Rick Dalton moment when I realised that parts of Torment and The Last Night (1983) were filmed in the same church as my last feature film, The Mire (2023). Seeing Butser Hill, Queen Elizabeth Country Park, and the old John Pounds scrapyard in Death Run (1987) made me contact MurLyn and ask for the opportunity to remake it. Speaking of which, if you’re going to check out any Michael J. Murphy film, Death Run would be my recommendation. It’s like Mad Max (1979), but set in Portsmouth, without the costume budget.

At this point, I’m running the risk of becoming the very thing I decried most in my initial auteur article; someone who takes auteur to mean ‘filmmaker I like.’ So, how does Michael J. Murphy’s work hold up against the criteria I set out for the auteur theory?

Auteur framework as applied to Michael J. Murphy.

Of Michael J. Murphy’s thirty-one known films, twenty-six are available in the Magic, Myth, and Mutilation box set (yes, I shamelessly stole the title) released by Powerhouse Films. The boxset is by far the most comprehensive collection of Murphy’s work. If it isn’t available in this set, it isn’t available. Therefore, my analysis of Murphy’s work within the context of the auteur framework is based on these twenty-six films.

Visuals

Let’s start with consistent visual style and motifs. It’s the easiest criteria for us to assess based on the body of work presented to us. It’s important to remember that Michael J. Murphy shot films for very low budgets and his access to grip equipment outside of a tripod was pretty much nil. Instead, Murphy took a handheld approach when creating movement in his films. This pervades the majority of his work on 16mm film, the use of a handheld camera runs throughout these films. Later on in his career, when he had shifted to MiniDV and HDcam, Murphy favoured tripod shots and the use of handheld footage became rarer. This is no doubt down to the fact that shooting handheld footage on MiniDV and HDcam looks terrible unless you’re at the widest end of the lens. It’s difficult to make it work, especially when shooting on interlaced video, which Murphy did. This is not Murphy’s fault and he was adapting to what he had to hand. Earlier digital cameras were almost all interlaced and you could only de-interlace them using expensive editing software. I remember shooting my first films on interlaced video and having to de-interlace every bit of footage in post.

Whilst discussing the visual style, it’s important to bring up the locations Murphy chose for his films. Location is important and the right ones lend a lot to the visual style of a film. Michael J. Murphy’s locations jump between three specific types of locations, each serving different story needs. The most prominent location is coastal Greece, a bright and idyllic location that lends an air to the exotic to his visuals. The coastline of Greece has hard rock edges that contrast with the deep blue of the surrounding oceans. They impose a very ‘fish out of water’ feel to the visuals.

The second most prominent location in Murphy’s films is isolated country homes occupied by very few characters. Again, Murphy uses this location for story purposes, creating a sense of isolation. The night shots of these houses achieve this doubly so almost by accident. Murphy’s lack of large lighting setups means the night outside the house is pitch black, adding to that sense of isolation.

Finally, Murphy set a lot of his films in the city of Portsmouth. Portsmouth is an island-based city and presents a unique visual aesthetic. Bombed heavily during World War II, the reconstruction of Portsmouth blends the old with the modern. Realising they couldn’t build outwards to accommodate the influx of people, they built upwards instead. This led to towering blocks of flats next to terraced housing, which in turn were next to tall country-style houses, and that’s before you reach the seaside mini-mansions. This use of location works well in the stories where Murphy tells tales of the dangers lurking around the corner, spurred on by the collision of the wrong people at the wrong time in such a crowded city.

There are exceptions, of course. Michael J. Murphy enjoyed making sword and sandal-type epics (he made three films based on the legend of Tristan and Iseult) and these are set in the wilderness, or sets constructed in Murphy’s garden shed/garage.

In my view, the use of three key settings for his films and shooting handheld on 16mm film, qualifies Murphy for this section of the framework. Admittedly, he doesn’t have any of the specific shots that we associate with many directors i.e. Tarantino’s trunk shot. However, the lack of budgets would have made this difficult.

Budget

Michael J. Murphy is one of those rare filmmakers whose work’s budget qualifies him for the auteur framework because it was so low. Some would argue that a higher budget allows filmmakers to express their voices more clearly than lower budgets. To an extent I do agree, if we look at Christopher Nolan's Following (1998) and compare it to Dunkirk (2017), we can see how much more of a Nolan film that is (some might argue that Dunkirk is the most Nolan, of Nolan’s films). In the case of Michael J. Murphy, I believe that his strengths come from his limitations.

If you look at his body, Murphy’s films thrive in taking three or four characters, putting them in isolated locations, and letting them play off against one another. The wheels start to come off when his aspirations go beyond that. Take Death Run, which is a personal favourite of mine, but it’s easy to see how the bigger idea means that Murphy doesn’t have as much control over what he’s doing. There is a risk that by having more money, Murphy might try to take it further and stretch himself beyond his means.

Themes/Ideas

Finally, the core aspect of auteur theory when analysing a filmmaker’s work. Whilst the previous two sections add to the auteur argument, it is the section about themes and ideas where the true argument is made.

Throughout his films, Michael J. Murphy alludes to a specific set of ideas and themes. At the most basic level, his work consists of stories about people who are out of place. This ties us back into the settings he uses in his films and how his three primary location choices invoke a sense of isolation and being a fish out of water amongst his characters. They don’t feel like they belong in the same strange settings, creating tension throughout the film.

Another consistent theme in Michael J. Murphy’s work is manipulation and control, especially within family units. Two of his films, Secrets (1977) and The Hereafter (1983) revolve around the manipulation of a young family member by their parental figure, post-mortem. Bloodstream (1985) is about a filmmaker, out to get revenge on the distributors who manipulated him and ripped off his work. In the excellent Torment, it is suggested that singer Anna Bell’s agent is ripping her off and keeping her drugged up to keep her churning out hit songs and a profit. In Death in the Family (1981) and Roxi (2004), we deal with the manipulations in a family unit, where we’re never quite sure who is responsible for what wrongdoing and who has the upper hand. Skare (2009) features two country club owners manipulating a lost young man who has recently escaped from an asylum. It’s a theme that Michael J. Murphy returns to again and again. One can’t help but speculate how much ties into Murphy’s personal life.

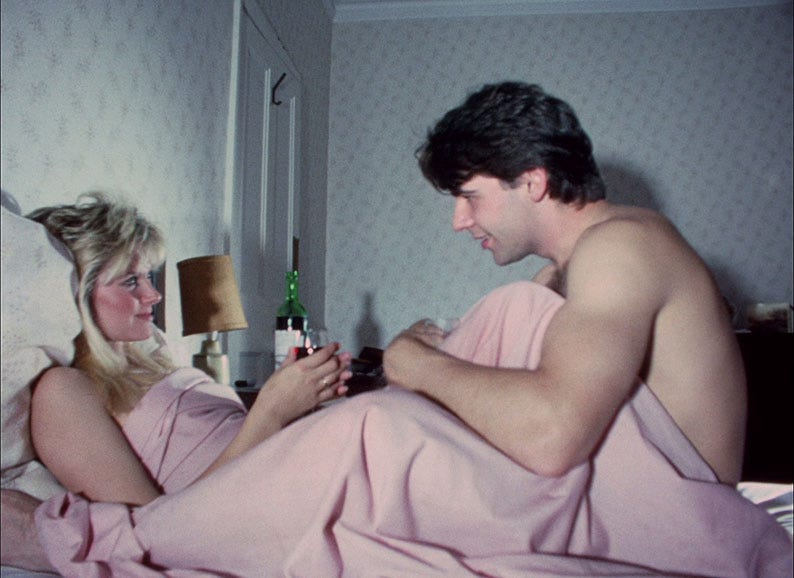

The final major theme of Michael J. Murphy’s work is that of forbidden love. Throughout his films, we see illicit affairs, and incestuous relationships, Road to Nowhere (1993) features a brother-sister sex scene. It’s all there, plain to see, the forbidden love often tying neatly into the themes of manipulation and control. However, the greatest example is Murphy’s interest in stories of forbidden love comes from his obsession with the legend of Tristan and Iselut.

The legend of Tristan and Iselut tells of Tristan of Cornwall, who was tasked by his uncle, King Mark of Cornwall, to escort Princess Iselut of Ireland so they could be married. During the journey, the pair ingest a love potion and begin an illicit affair. This Arthurian legend struck something in Michael J. Murphy’s mind. He revisited the story three times during his career, never quite feeling that he got the film right. The first time he tried to make the film was in 1970. Most of this film is now lost, the version in the Magic, Myth, and Mutilation boxset featuring a new score, title cards where dialogue should be, and a large portion of the footage comes from a VHS recording of a projection of the film elements made in Murphy’s home. Only nineteen during this first attempt at the film, it’s understandable why Murphy felt he hadn’t made it all the way.

Murphy would revisit the story in 1986 with greater control of the craft, but not the budget to make a film like this. Using a balsa wood boat with a bedsheet for a sail, shooting at night and framing to avoid showing the sea (or lack thereof), Murphy’s efforts are noble but still fail to satisfy his desire to do the legend justice. However, in 1999, Murphy tried once again to tell the tale of Tristan and Iselut using his brand of filmmaking, and this time he largely succeeded. Cast well, shot well, and given all the honesty and reverence one would a Shakespearian epic, 1999 delivers Michael J. Murphy’s true vision for the story. There are two versions of the film available, the original cut of the film and Murphy’s director’s cut. The director’s cut runs seven minutes shorter than the original cut. This is Murphy’s definitive version of the story, but he still wasn't done exploring the theme. Murphy continued exploring this theme right up until his final film. The Return of Alan Strange (2015) explores the effects of an illicit relationship on one’s career. It's a case study in resentment, the character Peter Hennessey holds a grudge against the man who replaced him on a TV show after he was fired for being gay. It’s interesting to watch Murphy’s interest in illicit relationships play out by exploring how backward and rock-headed our society’s thinking used to be.

All this considered, I believe I have made a brief, but convincing argument as to why Michael J. Murphy can be considered an auteur under my framework. The boxset, Magic, Myth, and Mutilation, is worth checking out. You get a lot of films, covering almost all of Murphy’s career, for a reasonable price tag. In exploring the films of Michael J. Murphy, you’ll no doubt find one of the most interesting, almost unheard voices in British cinema.