When I was about eleven years old, we joined a sort of mobile movie club. What this was, was a guy who had a massive movie collection renting his films to people. We would pay a monthly fee and each week the guy in question would drop off a video and collect the previous week’s. Every other month we’d be given a new copy of the titles folder, complete with bad photocopies of the covers for us to look through. It was a neat way to watch a whole host of films without paying through the nose or being refused because of the UK rating system. Our local video store was very expensive, and the titles I wanted to rent were rated fifteen or eighteen, so I had to go with my parents to rent them, and if the owner saw me selecting titles he wouldn’t allow us to rent them.

I don’t remember many of the films we watched whilst a member of this club, but two films, in particular, stood out: Slugs (1988) directed by Juan Piquer Simon, and Down Periscope (1996) directed by David S. Ward. These two films are vastly different in tone, genre, and narrative. Yet, of all the films we borrowed, these are the only two that still stick in my mind.

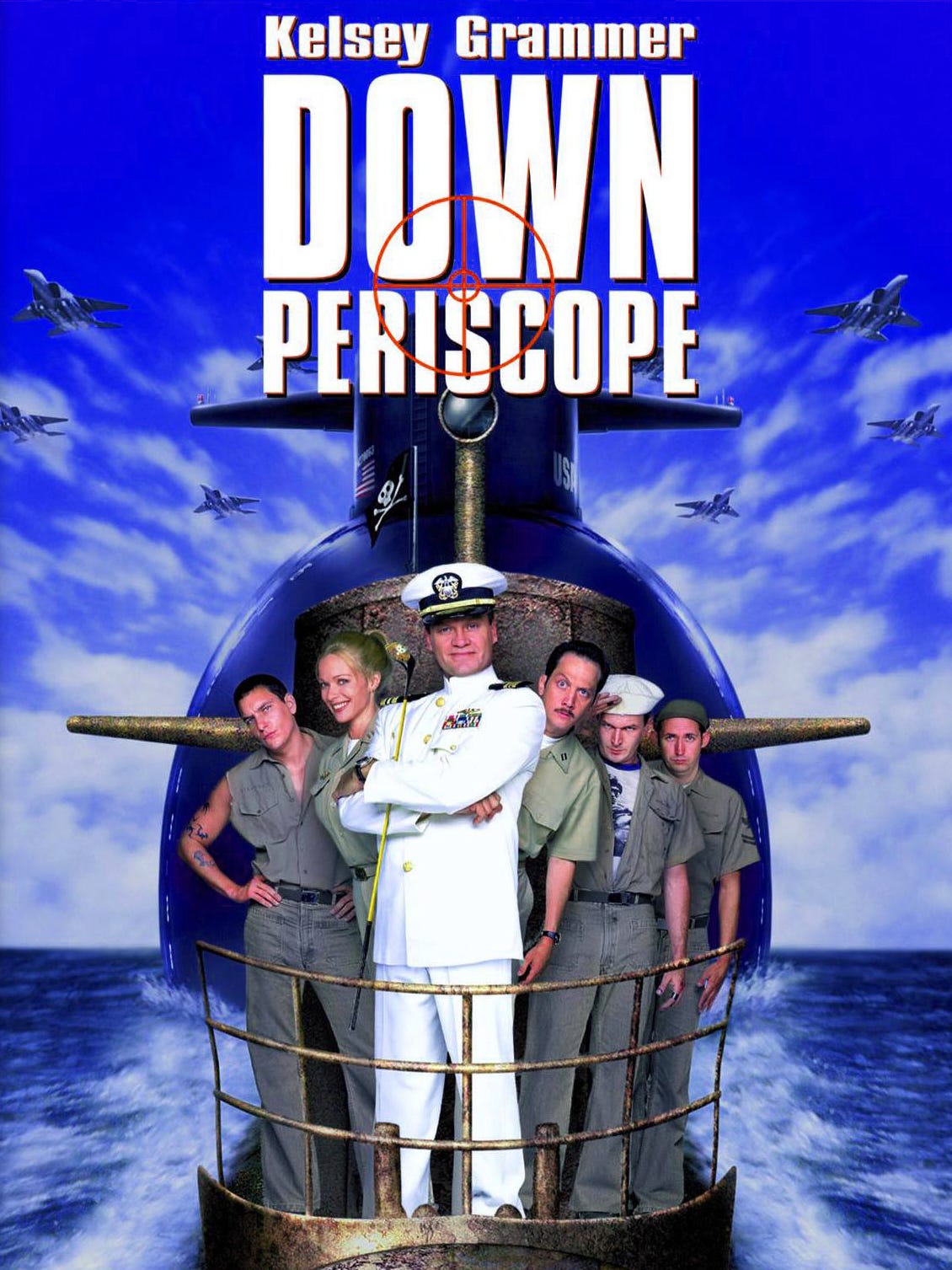

Down Periscope is a short, yet entertaining nineties comedy starring Kelsey Grammar. To look back at it now, the comedy is certainly dated, but when taken in the context of its time, the humour is still pretty silly. It follows a rag-tag group of the US Navy, the loser group if you will. You’ve got the fat chef (Ken Hudson Campbell), the weird sonar operator (Harland Williams), the grizzled old man who’s seen it all (Harry Dean Stanton), the one with the attitude problem (Bradford Tatum) and the first female submarine officer (Lauren Holly). They’re led up by Kelsey Grammer’s Tom Dodge and Rob Schneider’s Marty Pascal. Schneider plays the mouthy, arrogant second in command who believes he belongs elsewhere and is the ideal contrast to Grammer’s Dodge, the rogue captain who deserves to be higher up in the chain of command if only he could play by the rules.

It’s a standard setup for this kind of comedy, especially from that era. As a rule of thumb, comedy isn’t my favourite genre. I’m very particular about it and I don’t usually find stereotypical jokes funny. Fart jokes are well off my radar, but there’s a cracker in Down Periscope. Even though I don’t usually find this kind of film funny, something draws me in here and keeps me on the hook. It has me in stitches.

I think it’s a case of finding the characters relatable. I find something in the Tom Dodge character deeply relatable, even now. As a child I was notorious for not following instructions, I always wanted to do things my way and not the conventional way. Not much has changed as I’ve gotten old and those elements of Dodge’s personality still ring true, no doubt enhanced by Kelly Grammar’s pure charisma in the role. I would also argue that Down Periscope is a smarter film than it was ever given credit for.

The comedy of the time swung wildly between what I consider to be deeply crass humour. Humour using shouting, farts, and body fluids as the punchline to many of their jokes. The other end of the spectrum was the family-friendly, fairly flaccid fare that didn’t appeal to me either (I was ready for secondary school and wanted to appear cool). My preferred type of humour focuses a lot more on wit and satire. I like to understand the references films are making. Getting the shits in an awkward place has never been funny for me, my only real reference point for getting the shits is whenever I’ve had it, and none of those experiences have been good. So, it’s clear to see why getting the shits and other such body fluid jokes don’t appeal, as for humour based around shouting… I’ve always associated shouting with stupidity, even when used in comedy. Satire, social critique, and wit are my preferred vehicles for comedy, I love the works of Monty Python and Mel Brooks. I can’t remember how many times I’ve seen Blazing Saddles (1974), but it still gets me to belly laugh every time, I even find myself noticing jokes regularly. I like jokes that take the piss, that mock, that point out the problems in the world around us, or that reframe something familiar in a new and humorous light. I’m also a big fan of the absurd.

I give this rundown of the comedy I enjoy because it’s essential to my deconstruction of Down Periscope. Yes, the film does meet the expectations of the comedies of the time. There is a sequence about halfway through the film where the crew has to remain silent because they are being stalked by a far more advanced submarine than their own. The chef, Buckman, can’t help himself and is eating the food he’s prepared whilst everyone else is being quiet and he rips one hell of a fart. The sound rattles around the submarine and alerts the other submarine to their presence. The smell drifts through the submarine and the rest of the crew struggle to keep silent whilst putting up with the horrendous smell. It’s a pretty ordinary joke. Normally, I wouldn’t find this kind of joke funny, but in Down Periscope it works. It works because it’s not the joke in and of itself, the fart joke is in fact, the setup for a joke. Realising that they’re screwed if they can’t get rid of the submarine stalking them, Dodge has an idea. Earlier in the film, the sonar operator (conveniently named Sonar) has explained to Dodge that he likes to record whale sounds so he can ‘learn their language.’ What at first seemed to be a quick laugh aimed at mocking an oddball member of the crew, becomes the solution to their problem started by the fart joke. Dodge has Sonar recreate the sounds of the whales he’s been listening to. The accuracy of the sounds, coupled with the fart, convinces the submarine hunting Dodge and his crew that they are listening to a pod of whales and so they move on. This is one of the reasons I like Down Periscope so much. It would have been easy to make a mean-spirited, let’s laugh at the idiots who can’t control their flatulence, type comedy film. Instead, it’s a film about how the oddballs, when working together under a leader who believes in them, can achieve great things. I like that.

Down Periscope is on the side of the oddballs. It wants us to cheer for them, not mock them. This is most evident when we examine the antagonist characters. There are two in the film, the aforementioned Marty Pascal provides Dodge’s immediate foil. Pascal believes he deserves better than than the diesel submarine they’re given, on this Dodge and Pascal agree. But, whereas Dodge makes the best of their situation and aims to prove his worth through the adversity, Pascal takes it out on the crew, insulting and berating them at every opportunity. I’m not a fan of Rob Schneider’s work, just not my cup of tea, but in Down Periscope he captures the frustrated middle manager who is out of his depth perfectly. He perfectly encapsulates the ‘establishment’ Navy, who don’t approve of Dodge and his ways. This sub-plot wraps up perfectly when Dodge commits the ultimate act of rebellion and makes Pascal walk the plank. Whilst the sequence is the punchline of a joke, it also represents the moment that Dodge and crew become a whole unit. The Admiral at the start of the film tells Dodge to ‘think like a pirate’ and this is the moment that Dodge frees himself of the shackles of embarrassment, and embraces his role. Pascal represents the traditional Navy part of Dodge, his crew represents the side that gets things done. Dodge embraces the right part of him and goes to work.

The other foil, and the overarching villain of the piece, is Bruce Dern’s Admiral Graham. A traditionalist, a proper Navy man, who hates Dodge and all that he stands for. He wants rid of Dodge because he doesn’t stand for the orthodox manner in which the Navy operates, at the same time he knows he can’t just fire Dodge because he gets the job done. So, he decides to show him up during the war games they make Dodge participate in with the diesel submarine and oddball crew. Bruce Dern plays the snivelly, snide, arrogant know-it-all commander as well as one would expect from Dern, but the character feels unnecessary. The stakes are already there because Dodge and his team are in an inferior vessel and going it alone against the US nuclear fleet. Admiral Graham instigates the events by trying to force Dodge out but then doesn’t have much to do until the second half, where he commandeers one of the nuclear submarines to pursue Dodge personally. It feels a bit tacked on, Dodge’s victory with his oddball crew and the change they go through as a whole is worth the journey (as evidenced by Dodge’s insistence that he keeps his crew when he is given a nuclear class submarine to command) and Admiral Graham feels like the filmmakers following a template.

Down Periscope has long since fallen into obscurity. It’s unlikely that many modern film fans have seen it and more likely that most people who have seen it have long forgotten it. However, it is easily accessible in the modern age of streaming. It’s now on Disney+ and if you have the opportunity to see it, I would do so. Unlike other films of the time, the humour is quite grown up, the story quite heartfelt, and the performances a lot of fun. It also includes a theme song by the Village People, and who wouldn’t love that?

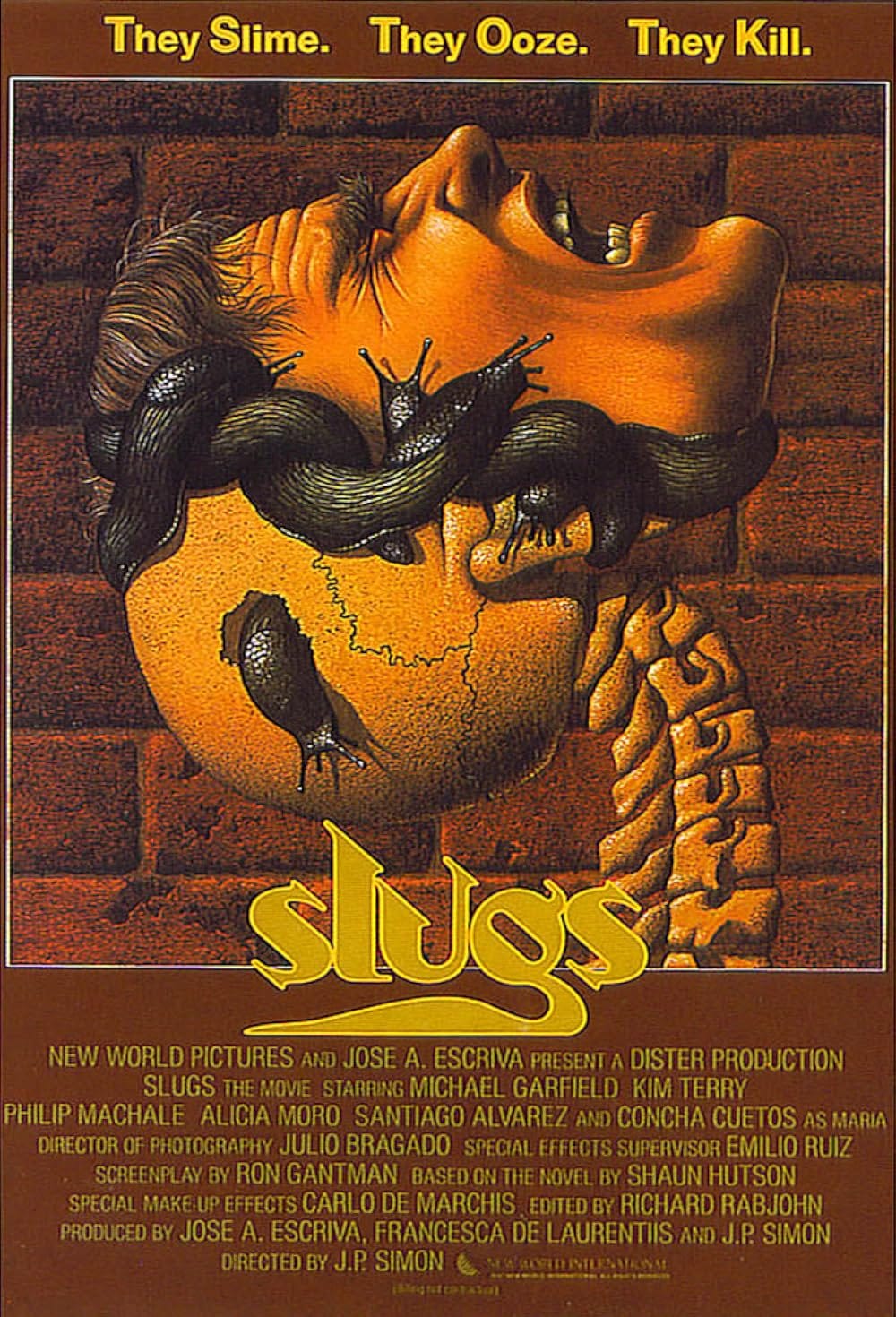

The other film that stood out from the mobile video rental catalogue was Slugs. People often laugh when I tell them that Slugs almost made it to my top 100 films of all-time list. I had to choose between it and Zombie Flesh Eaters (1979) by Lucio Fulci, Zombie Flesh Eaters is a real masterwork of Italian B-movie horror, deserving of any list. Not putting it on the list also means that as the list grows, Slugs will never make it on there as other films will be replacing existing films as opposed to films already on the list changing in rank order.

I remember everything about seeing Slugs in the folder. The artwork was captivating. Slugs crawling around a man’s head, his face contorted to show the pain he was in. At the time, I wasn’t a fan of horror films, gore and shocks would freak me out, but I did love creature features so Slugs got a pass. My mother was somewhat hesitant to let me watch it, but as ever my ability to nag and plead got around her and I found myself watching the movie.

I don’t remember much of the first watch. I remember thinking it was pretty cool and that the gore made me feel a little ill, there’s one sequence on a boat that stuck vividly in my mind for a long time.

We had Slugs for the week and the next time the folder came around it wasn’t on the list. It had snapped in someone’s VHS player and the guy couldn’t get another copy. Slugs is the type of film that could have easily disappeared into obscurity. It was an eighties, European B-movie with a small cult following picked up during its VHS run. It didn’t play in cinemas in the UK and opened on only seven screens in the US, and its opening weekend netted less than $16,000 according to Variety. It’s a wonder that there are any prints of Slugs left for us to see, however, in 2012 Netflix launched in the UK. Desperate for content, the streamer licensed anything they could to sell to the UK market, and one of those licenses was Slugs.

This is where I rediscovered the film. With a short memory of what the film was actually about, but also having since developed a love of gruesome and grotesque European horror films, I dived straight in and got so much more than I remembered.

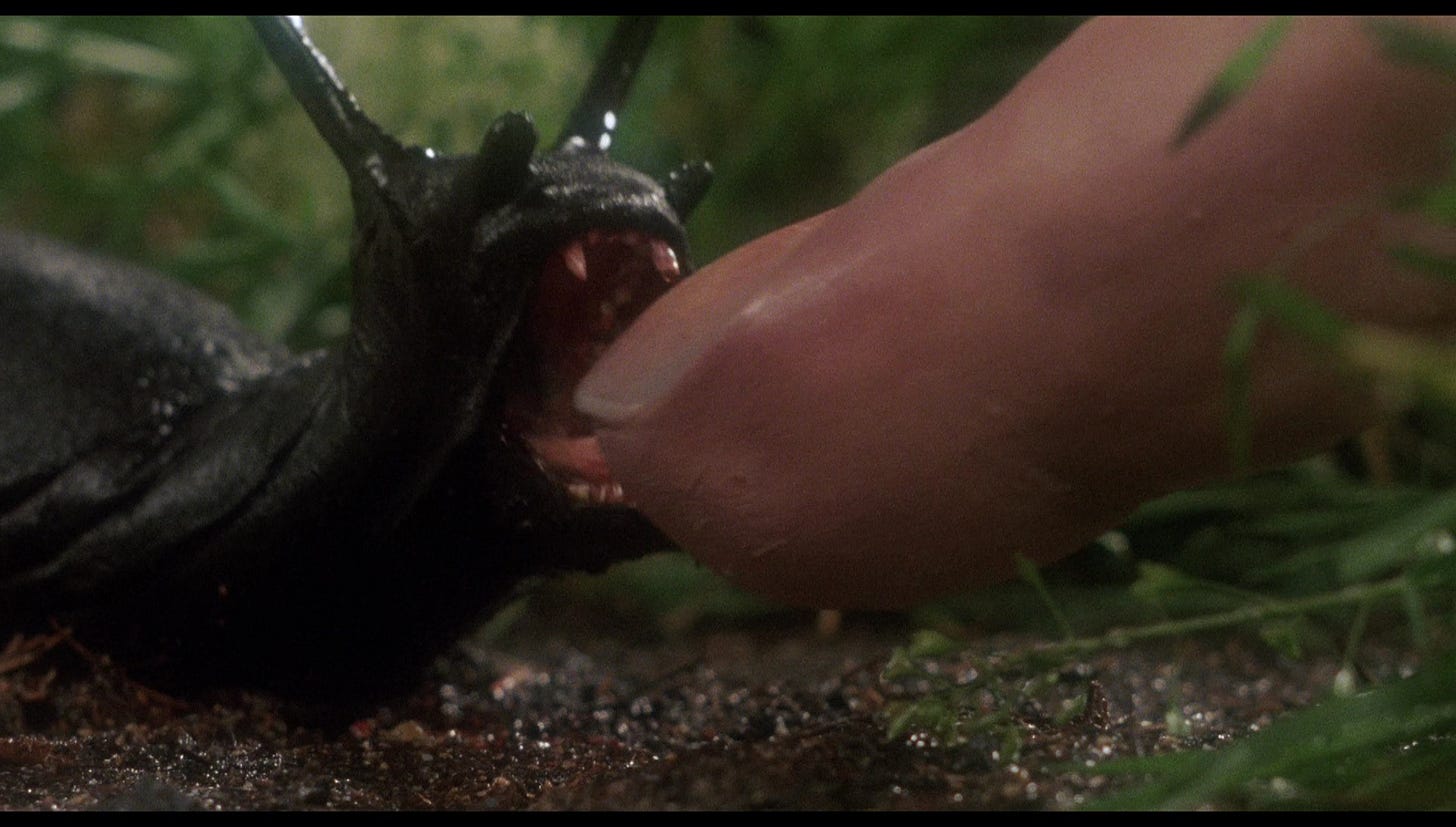

Slugs is the story of a small town, terrorised by carnivorous slugs and the efforts of local health inspector, Mike Brady, to stop them. It’s pretty straightforward in terms of narrative, but that’s not what the audience is coming to this film for. We’re coming for the blood and guts and veteran director Jean Piquer Simon delivers. Piquer Simon had already made the horror exploitation classic Pieces (1982) at this point, a film that carried the tag lines ‘you don’t need to go to Texas for a chainsaw massacre’ and ‘it’s exactly what you think it is,’ so he knows what he’s delivering.

There are some great horror set pieces here. The makeup and special effects by Gonzalo Gonzalo, Basillio Cortijo, and Carlos de Marchis easily rival the work of their US counterparts and in their native Spain even won a Goya award for their work. This includes the aforementioned sequence where the two teenagers are eaten on the boat. In traditional movie teen fashion they sneak onto a boat to cop off, but then find themselves trapped by the slugs who devour their flesh as they try to escape. Another sequence sees a gardener cause a chemical explosion because there a slugs hiding in his gardening gloves and once they latch on, they won’t let go. The best set piece, however, was created especially for the film and has no basis in the source novel. David Watson, one of Mike Brady’s friends, accidentally eats one of the slugs. Whilst preparing dinner, David’s wife cuts up the lettuce with a slug inside. It’s so great because David comments on ‘how odd the olives taste’ whilst eating, but we all know it’s a slug and feel suitably sick. Later in the film, David is at a very important meeting in a fancy restaurant, when he starts bleeding profusely, screaming in pain, then his head explodes, sending a torrent of worms everywhere.

It makes no sense. There’s no logic behind it. It is completely absurd and yet no one cares because it looks awesome, the practical effects as David’s head pops open and the worms blast across the room are fantastic. We don’t need a logical explanation because we’re here for the gore, and Slugs delivers.

Speaking of a lack of logic within the world of the film, something that’s always made me laugh is the lengths they go to to stop the slugs. A local high-school science teacher develops a lithium-based arsenic to kill the Slugs, the problem? The arsenic explodes upon contact with moisture and the slugs are congregating in the sewers. It’s elaborate. It provides an incredibly explosive ending to the film, but something has always bothered me.

No one, at any point during the film, suggests using salt against the slugs.

This may seem like a trivial observation for most, but it’s something that has stuck in my mind. We know what salt does to slugs, the sudden burst of active transport caused by the water being attracted to the salt turns them inside out. And whilst it may not provide the big, climactic explosion at the end of the film that the arsenic does imagine for a moment what it would look like if they dumped a few tonnes of salt into the sewer system. Imagine seeing all those slugs burst and turn inside out once. It would be a satisfyingly gory ending to the film that might induce vomiting in the audience. I know it’s a horror B-movie, and I know we shouldn’t take it so seriously, but part of me chuckles at the idea of this small, almost desolate town having to source an incredible amount of salt to deal with a wave of killer slugs.

Slugs is a somewhat faithful adaptation of Shaun Huston’s novel of the same name. The plot of the film is a lot leaner, removing a subplot about the slugs’ bites giving their victims a rabies-like illness. Instead, the film focuses on the slugs attacking people, it punches these sequences up to satisfy the gore hounds among us.

If you’ve seen Slugs, or plan to, and are in the mood for more slimy creature-based horror, I would wholeheartedly recommend Squirm (1976) by Jeff Lieberman. Squirm follows a string of attacks by violent, mutated worms across a small town in America. That’s pretty much where the parallels end for Squirm and Slugs so please don’t assume I’m accusing Slugs of copying any ideas, it’s just a bit of wider watching for you.

I recently revisited Slugs, this time in glorious HD, when I bought the Arrow Video boutique Blu-ray. Arrow does a great job of showing love to films like Slugs. They seem to understand that to many people, these films are important and that they have a place in people’s hearts. They treat the remasters with care. With my first experience of Slugs being a worn down copy on VHS where the picture was barely legible, to be able to sit and watch it in HD now, with every drop of blood flying at the screen, oozing from the wounds, and gushing from bites, highlights how far we’ve come technologically and how good these films looked back when they were made.

I miss the days of the mobile movie rental catalogue. It was a preface to what Netflix would be in the US and LoveFilm would be in the UK. I miss video stores, I sometimes think that having all the choices we have in streamers hinders my ability to choose which movie I want to watch. This was the final step in solidifying my place as a young cinephile. It would take a few more years before I would let go and plunge headfirst into the wider world of cinema, but I owe that first step to Slugs and Down Periscope.

References:

Greenberg, James (February 10, 1988). "Fresh Pics Stir Up National Boxoffice, But 'Nam' Still Tops". Variety. p. 3.