After last month’s long piece about David Gordon Green’s Halloween trilogy, I wanted to explore a smaller idea in this article. Whilst exploring the world of modern film criticism, particularly online, I’ve come across the notion of objective criticism. The idea that a film can be factually good or bad is a peculiar one when any kind of creative endeavour comes with an inherent appeal to one’s subjective tastes. However, when you look at the way the term is being used (something I don’t intend to replicate here as negativity isn’t what we do at the Apple Park Film Club), it becomes clear that it is being used as a stick to beat films with. This especially applies to films that dare to be inclusive or diverse in their casting, narrative, or themes. This is because these film critics follow a path of objectivism instead of objectivity.

Let’s start with an examination of what objectivism is and where its roots lie. Widely associated with Russian-American author Ayn Rand, objectivism is a philosophy emphasising the individual and their pursuit of happiness. It stemmed from Rand’s belief that humanity’s knowledge and values were an objective truth meant to be discovered instead of being created by our thoughts. Much like the rest of Rand’s work, it’s rooted in conservative ideals instead of progressivism and post-modern thinking.

According to Peikoff (1991 pp.4-11) Rand’s philosophy of objectivism stems from three axioms: existence, consciousness, and identity. Rand argued that these axioms served as propositions that defeated opponents arguments because they have to be acknowledged and used in any argument attempting to deny them. Peikoff takes this further and argues they are in fact inescapable because they are the base of all knowledge.

Rand defined the three axioms as:

Existence: observable and self-evident, it sits at the base of all knowledge. Existence, by its very nature, exists, and to exist is to have an identity. This identity is our first understanding of the law of non-contradiction and another crucial base for all knowledge. In 1992 Rand wrote: “A leaf cannot be all red and green at the same time, it cannot freeze and burn at the same time. A is A.” Because of this train of thought, objectivism rejects post-modern thinking, where ideas can be said to transcend existence.

Consciousness: Rand argued that consciousness cannot be established unless it is about an independent reality. Gotthelf (2000) argues that consciousness “cannot be aware of only itself - there is not ‘itself’ until it is aware of something else.” This definition of consciousness means that reality cannot be constructed by the consciousness, merely discovered. This means consciousness comes second to existence because the consciousness has to find something that exists.

Identity: Identity is the simplest of the axioms to define. Identity is used to define entities and these entities behave in accordance with the nature of their identities. If entities don’t behave per their identities, they are not that entity.

Where does this leave us concerning film? Whilst objectivism has never officially entered film studies discourse, the modern film critic seems to hold it close to their core values of film criticism. I’ve concluded this based on the epistemology of objectivism being rooted in reason. Rand wrote in her work The Virtue of Selfishness (1962 p 22) that reason is the faculty that integrates the material provided by man’s senses. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that objectivists form an understanding of the world through their experiences with the world and that this understanding becomes rigid. This may seem like a self-evident statement and a broad one that can apply to many ways of life. It’s when we pair this with the objectivist concept of ethics that we see how this applies.

The ethics of objectivism are centred solely on the self. Anyone who has read any of Rand’s work can attest to this. This focus on self interest exposes the objectivist lens that many online film reviewers view modern cinema through.

In her 2006 analysis of Rand’s ethics, Tara Smith argues that the primary virtue of objectivist ethics is rationality. Smith claims that Rand meant “the recognition and acceptance of reason as one’s only source of knowledge, one’s only judge of values, and one’s only guide to action.” (Smith, 2006, p. 7) This is why so many of these film critics hide behind the concept of ‘objectively good.’ They can use it as an argument of rationality to hide their prejudices. It’s not that they dislike seeing more women or people of colour starring in the genres of films they love, it’s because the writing or the acting is objectively bad.

This is where people who refute this argument say ‘But what if the writing is bad? What if the acting is bad?’ It’s a valid point to make, and in some cases, the writing or acting can be less than stellar. I won’t refute this argument. Sometimes acting is bad, and sometimes writing is bad. However, it seems oddly coincidental that in this group of modern film critics, the acting and writing being bad seems to correlate with women or people of colour being in leading roles.

It would be facile of me to simply brand these critics as racist or bigoted, despite what their attitudes may suggest. Other people make this argument far better than I could and the point of this piece is not to attack others, but instead to argue against the concept of objectively good as an argument. With that in mind, I want to make the argument that nostalgia for films of the past plays a heavy part in the formation of this worldview.

I don’t need to explain what nostalgia is, but it’s become clear how powerful a tool it can be when used to manipulate us. There are countless products, adverts, music artists, films and television programmes, amongst others that use nostalgia to capture an audience. Some successfully, others less so. In the film and television world, we’ve seen the rise of the legacy sequel (as discussed in my previous article) and revisiting old franchises to bolster ticket sales and increase viewership. It’s an idea that has worked well in some instances and significantly less so in others.

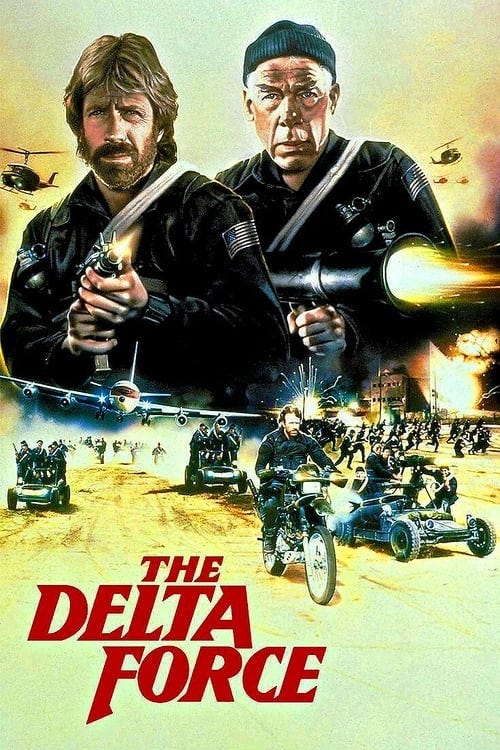

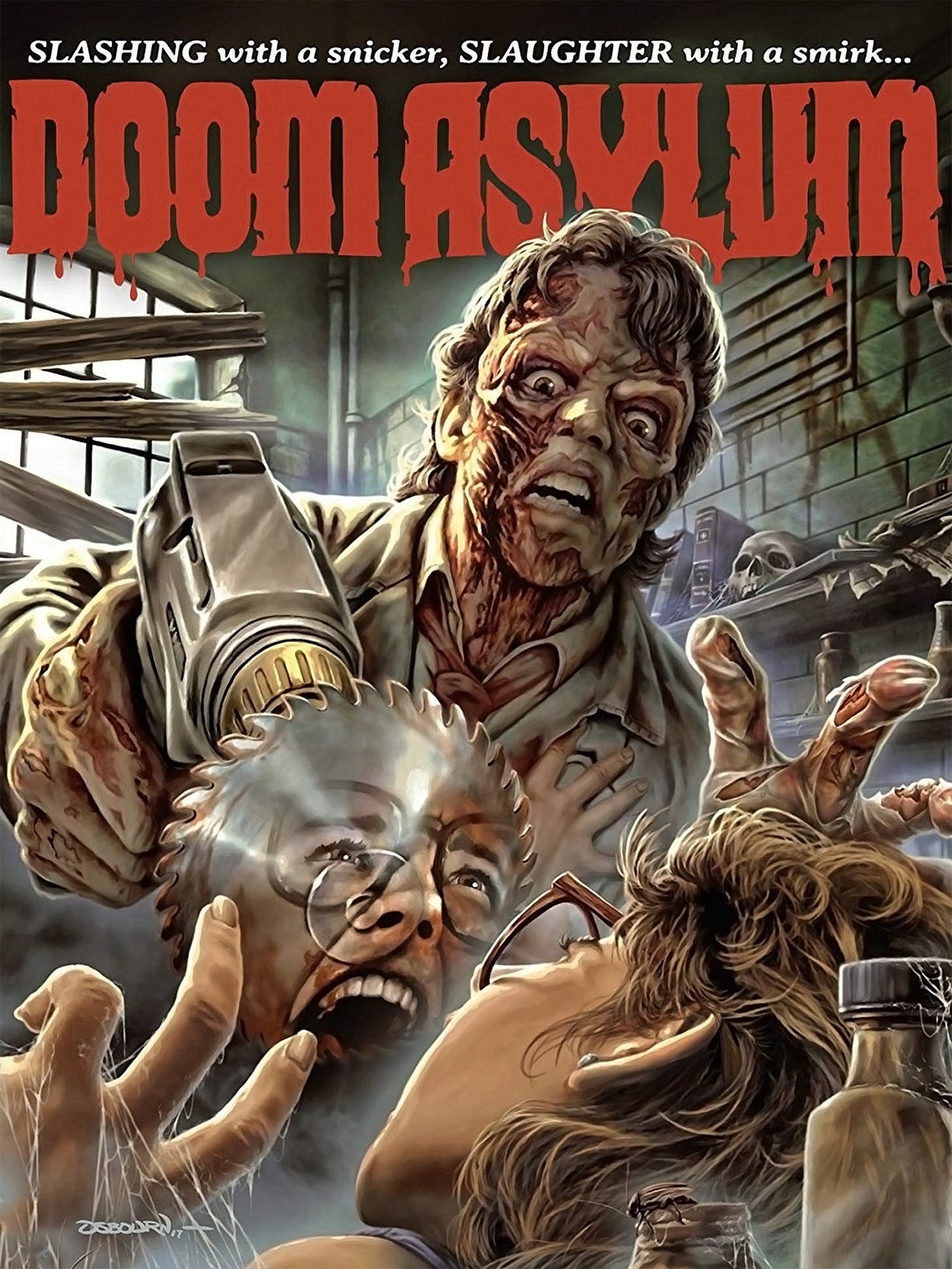

It’s this strong sense of nostalgia that anchors the tastes of some in the past. This isn’t necessarily a negative, people’s tastes are unique to them and to criticise a person for having particular tastes would be unhelpful. I feel a strong sense of nostalgia for my own childhood viewing experiences, which I discussed at length in the first four articles on the Apple Park Film Club. I’m not immune to it, I will always love Chuck Norris movies, but as a fan of the medium I won’t let nostalgia stop me from enjoying new cinema. As I’ve discussed in previous articles on the film club, I love cinema that no one would argue is objectively good. Slugs (1988), The Delta Force (1986), and Doom Asylum (1987) are not objectively good films. Doom Asylum is a horror film shot entirely during the day because they couldn’t afford a proper lighting set-up. Doom Asylum has ropey dialogue, pretty flat performances (but includes an early turn by Kristin Davies of Sex and the City fame), and cheap-looking make-up. Objectively, from a technical point of view, Doom Asylum is a bad film. It’s also a lot of fun and I get a real kick out of it every time I watch it. The Delta Force is one of my favourite films, and it is easily five stars for me in terms of entertainment. Like Doom Asylum, The Delta Force has many of the hallmarks of an objectively bad film: ropey dialogue, a beard led performance from Chuck Norris, and ropey writing that allows director Menahem Golan to re-write history. These film have objectively bad elements but are a lot of fun to watch.

Nostalgia has another effect on audiences as well. Nostalgia narrows our focus onto elements of a time that we like, allowing us to ignore the negatives we experienced from that period. Known as the Mandela effect, this phenomenon is essentially a misremembering of events or how things were. A lot of film critics, especially young ones, believe certain eras of film to be near perfect in their output, usually the 70s or the 80s. When looking back on the cinema of the 1970s and 1980s in the 2020s, it’s easy to believe that the output was nothing but hit after hit. This is because we naturally filter out the less good or lesser-known films. Everyone remembers Al Pacino’s excellent turn in The Godfather (1972) but a lot of people draw a blank if you mention The Panic in Needle Park (1971), in which he delivered an even better performance than he did in The Godfather (even if The Godfather is the better film). The same point applies to foreign cinema. The small group of modern critics this article is focused on likes to push foreign cinema as a beacon of quality, ignoring the fact that in the UK and the US, we only get the best of foreign language cinema. They ignore that Europe, Asia, and Bollywood have their share of cheaply made, low-budget, low-quality productions.

The irony is that in this reticence to engage with newer cinema, or the lower quality of foreign cinema, and instead focus on their nostalgic love of older films, they ignore one of the central doctrines of objectivism. Rand believed that attaining knowledge that existed beyond one's perception required volition (free will) and observation, concept formation, and then deductive reasoning. A process where proof identifies the basis in reality of any claim that one wants to assert is truth (Peikoff 1991 pp.116-121). By refusing to engage with these texts openly and honestly, they remove their argument from objectivism and objectivity.

In short, they’re little but bullshit.

References:

Gotthelf, Allan (2000) On Ayn Rand.

Peikoff, Leonard (1991) Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand.

Rand, Ayn (1962) The Virtue of Selfishness.

Rand, Ayn (1992) Atlas Shrugged: 35th Anniversary Edition.

Rand, Ayn (1996) For the New Intellectual: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand.

Smith, Tara (2006) Ayn Rand’s Normative Ethics: The Virtuous Egoist.