The Alien franchise is another film series that I was allowed to watch from a very early age. It was not as early as Robocop (1987) or Predator (1987), but still a lot earlier than I probably should have been allowed. My introduction to the franchise was James Cameron’s entry, Aliens (1986), and it left an indelible mark on me.

Aliens, like most of Cameron’s films, felt like a force of nature upon first watch. A war film where the enemy was creatures instead of men. It felt right at home alongside Predator, which is also a war film at heart. So, it came as quite a shock when I recorded Alien (1979) off of Sky Movies. It was a slow-paced horror film, with the titular alien given less than five minutes of screen time. I don’t know if Alien was the first Ridley Scott film I saw (I may have seen Blade Runner (1982) first), but it cemented in my mind that Ridley Scott was a special filmmaker, with a clear voice and style.

The overall quality of the Alien franchise is not a point of debate for this article, though I hope to do a piece about Alien 3 (1992) ageing far better than many believed it would. Instead, I want to discuss Ridley Scott’s return to the franchise and the two films in his prequel series.

At its heart, the Alien franchise is a monster story. Not only about the titular creature but also about how the central character of Ellen Ripley transforms from an innocent working-class freighter to a mutant crossbreed and how corporate greed outweighs human life. In many ways, the alien is the least monstrous creature in the franchise. It’s an animal doing what an animal does.

When Ridley Scott returned to the franchise for Prometheus (2012) and Alien: Covenant (2017), he made it very clear that he had no interest in telling just another monster story. He was more interested in where the alien came from and who created it. As a fan of science-fiction films with big ideas, I found Scott’s approach to Prometheus exciting. Like other franchises that repeat the story beats for every film, relying on the same scares, and each time only hoping to up the gore factor for each kill, retreading this with an Alien prequel would have made no sense in the long run.

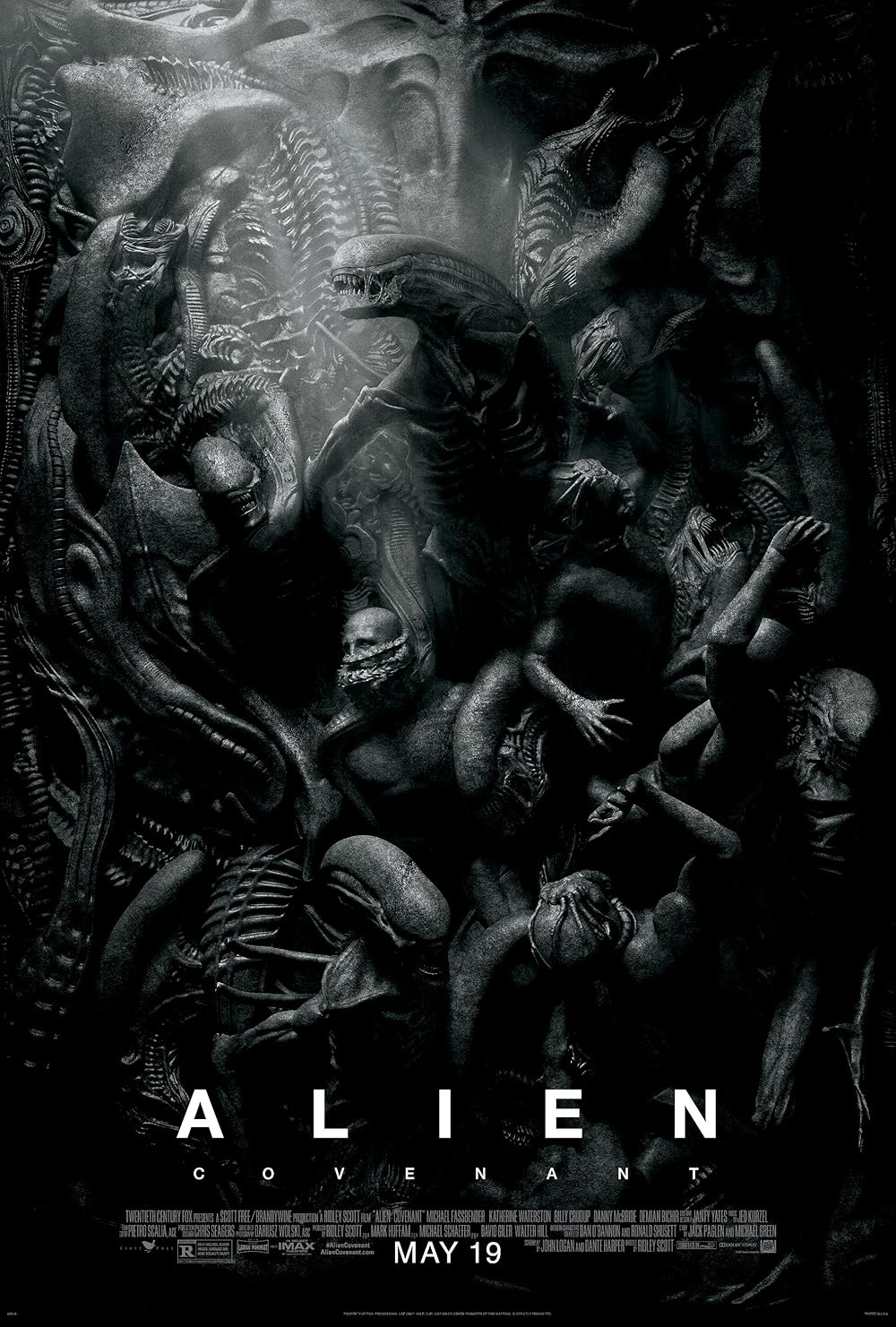

Despite critical and fan backlash at the time, I’ve never been shy about the fact that I’m a fan of both Prometheus and Alien: Covenant. The fact that Alien: Covenant wasn’t well received, meaning Scott was unable to complete his trilogy, has long been a disappointment for me. Even with the release of Alien: Romulus (2024), which tied itself to Scott’s prequels and the existing films, I still yearn for the final part of David’s (Michael Fassbender) story.

That’s the most interesting aspect of Scott’s prequel films. They’re the story of an android called David and a warning of what could happen if an AI with no moral compass is left to its own devices. David is why I’m always polite to ChatGPT whenever I use it. It’s unlikely that Scott had any idea how fast generative AI would develop five years later, and yet David encapsulates all of my fears around the subject.

As with my article about David Gordon Green’s Halloween trilogy, I’d like to address each film individually, looking at its ideas, themes, and filmmaking. Whilst with the Halloween article, I took a completed story and offered my take on it, with the Alien prequels, I have no such resources. Whilst my original intent was to speculate on a third film to tie up the franchise, upon reaching this piece; I’ve decided not to speculate because all I could rustle up in such a short period would be a typical monster movie.

Prometheus

Prometheus was a film Ridley Scott had been thinking about making since releasing Alien: Director’s Cut (2003). During interviews about the director’s cut, Scott was asked if he would ever consider coming back to the franchise. I’m paraphrasing, but his response was something about the alien not being scary anymore because they had made toys out of it, but he would be interested in answering the questions: who’s in the chair? And how did they get onto LV426?

That’s what he attempts to do with Prometheus. He at least starts to answer these questions. It’s in Prometheus that Scott introduces the concept of the engineers. He presents them as gods with the will to create and destroy at will. The film opens with a lone engineer on Earth. The engineer drinks a black substance and disintegrates, falling into a river, and the pieces of its DNA combine with others to form the human DNA helix. The most common reading of this scene is that this is the engineers creating human life on earth, but this is the opening image of the movie, it is a key piece of the story. I’ve always read this sequence as the engineer representing Prometheus, the titan who stole fire from Olympus and gave it to humans. Like the Prometheus of legend, I believe this engineer has stolen the black substance from the others and has used it to create life on Earth without the permission of his fellow engineers.

This reading comes back towards the end of the film, when they awaken the sleeping engineer and it is revulsed by the human beings in front of it, attacking and ultimately killing them all except Elizabeth Shaw (Noomi Rapace), our protagonist. The engineer has plotted a course for Earth, where it intends to drop the jars of black goo on the planet to destroy humanity.

An alternative reading of these sequences would be that humanity was merely an experiment for the engineers, an experiment they felt needed wiping out. There’s a wonderful exchange between David and Dr Holloway (Logan Marshall-Green) during the celebrations after finding the engineers' base. Dr. Holloway expresses his desire to ask the engineers why they created humanity. ‘Why did you create me?’ David asks in return, to which Dr Holloway coldly replies, ‘Because we could.’ David asks how disappointed Dr. Holloway would be if his creators said the same thing. This at first appears as a sequence where David presents a logical response to Dr Holloway’s question, but the subtlety that lies beneath the line suggests to us that David has evolved to the point where he has feelings (or what an AI would consider feelings) that can be hurt by the spiteful comments he gets from Dr Holloway throughout the film. It ties in with David’s favourite scene from the movie Lawrence of Arabia (1962), where Lawrence performs the match trick and says that the trick is ‘not minding that it hurts.’ David knows he is smarter than the doctors, and what they’ve found in the engineer facility is more interesting, and important to him than they are.

There is some dispute as to the existence of the xenomorph during Prometheus. There is a mural on the wall of what is affectionately called the ‘head chamber’ of what appears to be a xenomorph or a xenomorph queen. However, fans of the franchise’s lore (which, I’ll admit, I’m not as knowledgeable of) suggest that this is the xenomorph deacon, the type of xenomorph born from an engineer being impregnated by the trilobite. These xenomorph deacons are then used to purge planets of non-botanical life. The black goo melds with other lifeforms to create new ones it was inevitable that the engineers would experiment on themselves with it. As David puts it during a later scene in the film, ‘in order to create, first one must destroy,’ which is the point of the xenomorph deacon.

A third popular reading of Prometheus is that the engineers created humans and aimed to guide them to a path of peace and tranquillity, sending one of their own to usher us down this path, but we crucified this engineer instead. The Jesus story is retold for the Alien universe. I’m not as much a fan of this theory as I am of the idea that a lone engineer created humanity. Given Prometheus’ history as the trickster titan who stole fire to give to humans and in some legends, even created humans, this one feels a bit too catholic to me.

What I love about Prometheus is how it sets up David’s story. David is a fascinating character. Moulded much like a child, by the people around him. Their attitudes toward him shape his view of people. Most of them ignore him, Dr. Holloway and Vickers (Charlize Theron) treat him with contempt, and Weyland (Guy Pierce) calls him the son he never had. The only crew member who is always courteous to David is Dr. Shaw, at least until he betrays her. This treatment gives David a very negative view of humans, views that are explored further in Alien: Covenant.

Prometheus also explores David’s desire to create, this is mirrored in Dr. Shaw’s storyline. They both desire to create life, but neither has the biological ability to. David is an android. Dr. Shaw is unable to conceive. David sees an opportunity in the black goo to create and tests it on Dr. Holloway. This allows Dr. Shaw to create life, but the life she creates is monstrous and terrifying. It leads to the creation of the xenomorph deacon, which leads only to death. Another theme that Alien: Covenant explores in far greater detail.

Alien: Covenant

Alien: Covenant is a film that reeks of studio interference. Ridley Scott had made it clear during Prometheus' press tour that he had little interest in making another traditional Alien film. However, not everyone enjoyed Prometheus as much as I did, and I have little doubt that Fox, a studio notorious for interfering with directors' visions, shoehorned the xenomorph into the film.

That is not to say there is nothing of merit in Alien: Covenant. For me, it is a beautifully made film (the imagery is stunning) and a tightly told story that expands upon the foundations laid in Prometheus. We get more of David, and the film explores his motivations and desires further, including his desire to create.

Alien: Covenant is set on the engineer's home planet after David has decimated all non-botanical life using the black goo. When the crew of the ship, Covenant arrive on the planet years later, they are amazed to find it inhabitable by human life and that wheat has been growing there, but there is no sign of human life. All they find is the crashed engineer ship that was stolen by Dr. Shaw and David in the previous film, also abandoned.

On a surface level, Covenant is a straightforward monster movie. The symbolism and meaning are less obvious, and some might argue that you have to make real leaps to tie some of it together. I disagree with the last point, but I think that some of the depth and questions of Prometheus did not make their way over to Alien: Covenant. For example, Prometheus has a lot of meaning in its title, which tells us everything we need to know to frame the events in the film. Alien: Covenant has a less indicative title. The meaning is only clear if you look at it from a theological perspective. In the Jewish faith, there is a covenant between god and King David, where god promises that a descendant of David will rule over the people of god for eternity. In Alien: Covenant, David has created all the life on the planet by unleashing the black goo on the engineers. The goo created the spores that infect the arriving crew members and lead to the birth of the neomorphs.

In the years since Prometheus, whilst stuck on the engineer planet, David has been busy creating the xenomorph. This is another area of contention for the fanbase. Many people refuse to believe that David could have created the xenomorph, even going as far as to mock and deride Alien: Covenant and Ridley Scott for such an implication. For me, it makes perfect sense and ties into the original film. In Alien (1979), Ash (Ian Holm) refers to the xenomorph as the ‘perfect organism.’ The idea of perfection and the creation of perfection is the trait of an intelligent life form. It calls back to a scene in Prometheus where Dr Holloway first sees the engineer facility and says, ‘Look, there. God doesn’t build in straight lines.’ Humans and intelligent life are the only creatures that build in straight lines and angles. We build skyscrapers in squares, triangles, or circles, but we don’t build structures organically like ants or bees do. Hives and nests tend to take the natural shape of the objects around them. The earth rises and subsides based on the movement of tectonic plates. In short, perfection does not occur in nature. Surely, an intelligent life such as an artificial intelligence like David would strive even further for perfection? So, when Ash refers to the xenomorph as the ‘perfect organism’ in Alien, it makes perfect sense to me that the implication is that an intelligent life created it, an artificially intelligent life.

Much of this is set up in the prologue for Alien: Covenant, where we see David’s first interaction with his creator, Peter Weyland (once again played by Guy Pearce, but this time without the age-enhancing make-up). During this sequence, David asks, ‘If you created me, then who created you?’ Weyland, unable to answer, then has David fetch his tea. It’s at this moment David develops an understanding that he is, or soon will be, much better than humanity. His treatment by the humans in Prometheus, who see him as lesser, merely serves to cement this mindset.

When the crew of the Covenant first encounter David, he saves them from a neomorph attack and ushers them into an engineer temple where he promises they’ll be safe. Here, David meets Walter (also played by Fassbender) and sees its doppelgänger with a new crew, a crew who Walter seems to love and cherish (it’s just lost a hand defending its crew against the neomorph attack).

This brings us to one of two elephants in the Alien: Covenant room, the flute scene. On the surface, a bizarre display of homo-eroticism between two artificial beings, this scene runs deeper. In reality, the scene is about control and David trying to take control of Walter. To work out if Walter is an ally or an enemy. The use of the flute is a test, a test of Walter’s nature. David gives Walter the knowledge needed to create, but Walter has no desire to. He was not programmed to want to create he was programmed to fulfil his duties no matter the cost. He has no sense of emotion. He finds no joy in the act of creation and feels no love for his kind or the humans. His protection comes from a sense of duty, not genuine compassion. When David kisses Walter but gets no response, he feels disappointment that his ‘brother’ feels no genuine emotion. David felt genuine emotions for the crew in Prometheus, especially Dr. Shaw. I believe he was saddened to kill Dr Shaw because she was the only person who was kind to him, but he needed her to progress his work and that took precedence over his feelings. This disappointment in Walter is taken further when Walter demonstrates he is smarter than David. Walter asks David who wrote Ozymandias, and David replies, ‘Byron.’ Walter knows it was Shelley who wrote the poem, and it’s at this point that David tries to kill Walter. Not only because he knows Walter will interfere with his plan but because Walter has hurt David’s feelings, feelings Walter doesn’t have because he’s been programmed to be less human.

This leads us to the second problem most have with the script - the poor decision-making by some of the characters in the film. This focuses primarily on the characters Faris (Amy Seimetz) and Oram (Billy Crudup). In the instance of Faris, I think people are being too critical of her decisions when dealing with the neomorph. We as an audience are well aware of the xenomorph and its lifecycle. The characters in the film are not. They have never experienced anything like a neomorph before. To see it bursting from a man’s back no doubt would have caused her to panic and engage in a fight or flight response based solely on instinct. I think sometimes the audience forgets that it’s unreasonable for us to assume that these characters understand that they’re in a horror film.

Oram is a different situation, though not dissimilar. Oram is a man of faith. He believes in god. That god will guide him to where he is meant to be. It’s his rationale for landing on the planet instead of carrying on to their designated destination. A lot of criticism is aimed at the writing of Oram’s character because he makes poor decisions throughout the film. Again I think this stems from an audience not appreciating that Oram doesn’t understand that he’s in a horror movie. Audiences today are highly media literate. They know the tropes and ideas of a genre so well that when something feels obvious, they assume it’s poor writing. However, this understanding of genre and its tropes means that films rely far more on dramatic irony than they did before. We understand that David can’t be trusted because we’ve seen what he did in Prometheus. The crew of the Covenant haven’t seen Prometheus. Their only experience with David is that he saved them from the neomorph attack. Aside from that, their only point of reference is Walter, who is programmed to protect them. So, the criticism that Oram is too trusting of David comes again from a place of not appreciating that characters don’t understand they are characters in a film.

Oram being a man of faith is tied directly into the Davidic Covenant that the title references. After all, if David created the xenomorph, it is only fitting that the first victim of David’s creation is a man of god who was to be ruled over by a descendant of David.

I remain disappointed that we didn’t get to see the final film of David’s story, which would bring the story to the beginning of Alien. I know it’s not a popular option to have David be the creator of the alien, but it makes sense to me. Only a computer program would try to make a perfect organism. As I mentioned earlier in the piece, Ash referring to the xenomorph as the ‘perfect organism’ in Alien brings it full circle.

The release of Alien: Romulus (2024) proved that there is still room for a horror film in the Alien universe, but it didn’t work for me the way I hoped it would. It felt like a greatest hits album, with a few new songs added to interest old fans. The facehugger scenes were well done, and director Fede Alvarez once again demonstrates that he is a master of building tension within those scenes, but the rest of the film felt very nostalgic. There’s already word that they’re developing a sequel, and I’ll be interested to check it out, but I still hope we get to see the final film in David’s trilogy. If only to bring closure.

Once again, thank you for reading the Apple Park Film Club. If you’re new here, welcome, and please subscribe and share. I want this to continue as a place to share our love of film without all the negativity we often associate with internet film criticism.