The mid-2000s through to the mid-2010s saw the rise of a new genre of film known as New French Extremity. The term, penned by James Quandt in his article Flesh & Blood: Sex and Violence in Recent French Cinema, was used to describe the increase in both sexual and visceral violence in French cinema during the early 2000s.

While often associated with horror, the genre had a far subtler start (as much as it could be considered subtle) in the works of thriller and drama filmmakers, including one of my favourites, Francios Ozon and Bruno Dumont. As filmmakers, they started to incorporate visceral and extreme imagery into their films to shock the audience into an awakening from their lives. (Quandt, J). One of the most famous films from the new French extremity is Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible (2002). Often labeled as a horror film, Irreversible is a revenge film that philosophises on the premise that time destroys all things. Like Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000), Irreversible tells its story in reverse, forcing us to see the conclusion of a horrific series of events before the narrative unspools and reveals the acts and revelations that lead to such violence. Irreversible is a horrific film with scenes of extreme violence, but at its heart, is a drama about a man reacting to the violent rape of his pregnant girlfriend, not a horror film. New French extremity grew out of a desire to show the extremes that occur in the lives of ordinary people and shock us into the revelation that horrible things happen to everyday people.

The advent of torture porn in American cinema in the mid-2000s led to French filmmakers engaging with and incorporating elements of these films into their own. The ultra-violence of films such as Saw (2004) and Hostel (2005) influenced popular films of the later new French extremity such as Martyrs (2008) and Frontier(s) (2007), both of which descend into sequences of torture and violence. Martyrs (along with Irreversible) is one of the few films that made me feel genuinely uncomfortable while watching it. The difference for me is that I find the horrific nature of Irreversible to reveal an inherent truth in the theme of ‘time destroys all things,’ while Martyrs feels like violence for the sake of violence. I have discussed Martyrs with others who believe the films to have deep philosophical themes around the nature of faith, but I struggle to see past the violence when considering the film. The final image will forever haunt me and, while I can’t argue that Martyrs didn’t have a profound effect upon me, I can safely say I never want to see it again. Much like Irreversible, my copy of Martyrs sits amongst my collection of films, gathering dust.

An examination of the roots of the new French extremity can be found in Quandt’s article (linked below), but it’s important to break the belief that these films were merely horror films. I do this because the film I want to focus on in this article is often mentioned alongside other films in the New French Extremity but shouldn’t be. It is not extreme, but it does tap into one of the most basic human fears.

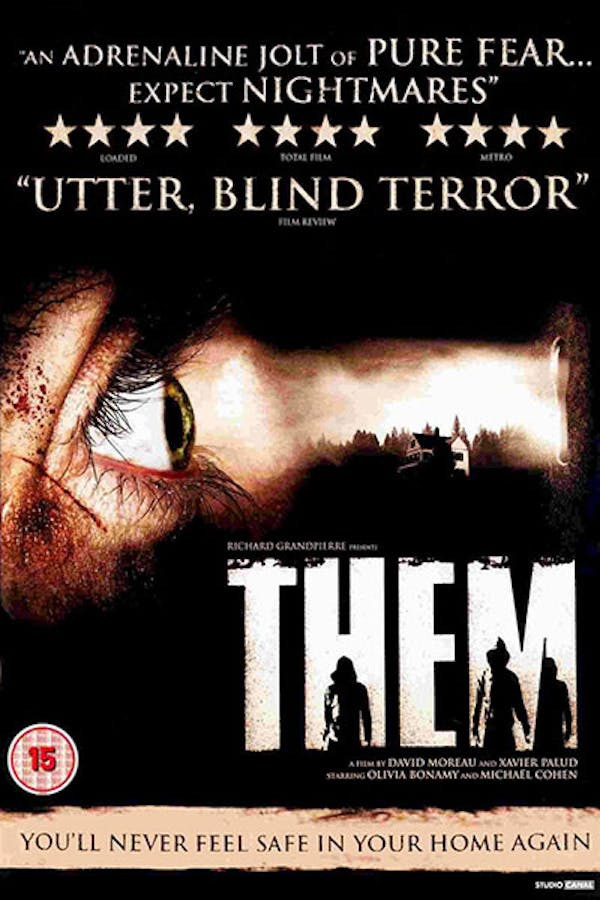

Ils (Them in English) is a 2006 horror film directed by David Moreau and Xavier Palud. It’s a French-language film set in Romania. It follows the simple premise of a couple alone in a big country house, running and hiding from a group of unidentified children who have broken in to hurt them. Despite its inclusion with the new French extremity, there is little bloodletting or violence in Ils, which is why I am so fond of it. I’m no fan of the new French extremity and, despite seeing a lot of films in the genre (at least enough to form a judgement), I find it hard to take any enjoyment from the genre. I don’t want to dwell too much on this as it’s not what the film club is about, but the marketing for Ils on its initial UK release sold the film using its inclusion in the extreme cinema of the time. It’s a big part of why I didn't see Ils on its initial release. Which, in hindsight, can only be described as a shame. For my money, Ils is a masterwork in visceral tension, and that’s why it works so well.

On the Making of Ils special feature on the home release, Moreau and Palud talk about how, when creating Ils, they asked their friends what their greatest fears were. The majority of the friends they asked said their greatest fear was someone breaking into their house, their home. It’s this primal, human fear that we all have that connects us to the characters and circumstances in the film. It is unlikely that many of us will find ourselves forced to hide from the police in a rural inn run by torturous Neo-Nazis (Frontiers) or find ourselves locked in a basement at the mercy of a cult seeking knowledge of the afterlife, flayed of our skin so we can begin to cross over and inform them of what waits beyond (Martyrs). However, we might find unwelcome guests in our house one night as we sleep. The idea may seem simple, but it’s in this simplicity that the film is so effective. By stripping back all the extra stuff, all the big ideas and philosophising, all the gory set pieces, and focusing on the raw human emotion of the premise, Moreau and Palud create a situation that evokes fear from the outset.

The writers took their fundamental premise and combined it with the true story of Romanian street children. Beneath the streets of Bucharest, hundreds of children lived, earning what little money they had through begging and prostitution. According to their website, the International Labour Organisation aimed to reintegrate as many of these children back into their families as possible, but only one in ten children made it that far. Many of the children were too old or too used to life on the streets that they could not be brought back into the fold of society. Moreau and Palud set Ils in Romania to use this issue and add facelessness to the invaders. This facelessness ramps up the fear. There’s a belief that the majority of murder victims know their killer, while this may be true in real life, in fiction the idea of the faceless killer is far more effective. Having children be the antagonists grinds down our sense of hope. Children are supposed to be innocent, so why are they breaking into this couple’s house and tormenting them? The film ends with a title card explaining that the children did what they did because ‘they didn’t want to play with us.’ It’s a chilling thought, that these children would be so far removed from society by living underground that to them playing is murder. It adds an extra layer to an already terrifying premise. However, in hindsight, attaching the film to the problem of Romanian street children feels unnecessary and in many ways, lacks decorum. It’s probably safe to say that such associations don’t help the efforts of the International Labour Organisation. That said, one should never allow reality to trump drama in fiction and the inclusion of Romanian street children in the film may have brought more awareness to the issue.

So, we have a premise that anyone can relate to, centred around a fear we all have, and a faceless enemy in the Romanian street children. Moreau and Palud have set the stage for their film. As scary as the premise and the nature of the villain are, it’s nothing without the right execution and the filmmakers nail both the macro and micro elements of filmmaking in Ils. My biggest gripe with films in the new French extremity and torture porn genres of film is the focus on nasty things happening to horrible people. I understand why, these films were made for the audience to enjoy the violence. It’s hard to enjoy violence being committed against characters we like, so it’s important to make sure the characters are people we hate, that way we can enjoy their torture. This doesn’t work for me and the reason my favourite slasher film is Halloween (1978), is because it spends a long time encouraging us to engage with the girls being stalked and killed, so when it happens we’re scared for them. Ils avoids this issue by presenting us with Clementine (Olivia Bonamy) and Lucas (Michael Cohen), a loving couple who live alone in the Romanian country. Clementine is a teacher and Lucas is a writer, two professions that it’s hard to dislike. The film spends a long time after its throat-gripping opening establishing Clementine and Lucas as characters we should care about it. I want them to survive, I worry about them when the kids arrive and every time the shit hits the fan.

Once Ils finishes the setup, provides us with a couple to care about, and settles in for tension, the remainder of the film unrolls as an almost perfect example of how to keep ramping up the tension. Moreau and Palud wrote the script with the layout of the house in mind. They knew how long it should take to reach the end of the hallway from the bedroom. How long it should take someone to get up and down the stairs. They knew the location like the back of their hand and wanted to present the events in as real-time as possible. This almost real-time experiment ups the ante further as we’re forced to watch our protagonists run the length of corridors, stairs, and through the woods surrounding their house, knowing that there’s no cut coming to compress time and thus leaving Clementine and Lucas vulnerable.

Moreau and Palud chose to shoot the film on lightweight, shoulder-mounted digital cameras, giving it a very real and documentary feel. This is exacerbated by their use of natural lighting and underplaying the mise-en-scene to make the house feel ordinary, and that anyone could live there. They underplay the use of music, bringing us into the moment and not having an element from outside the world of the film telling us how to feel. Instead, we’re treated to an effective use of low-key lighting to hide the invaders amongst the shadows and make us question what we see throughout the film. The freedom of the shoulder-mounted digital cameras allowed for long takes that could roam through the entire set, yet every frame, every camera movement, is deliberate and essential to the tension.

The terror starts as Clementine hears noises outside. One of the children has a clacker, that he likes to spin very slowly. It’s an effective use of sound to create an eerie feel and as the film progresses, the use of the clacker becomes like a dialogue between the teenager and his friends, as though he’s telling others where to look. As they investigate the sounds, Oliver notices that their car has been moved away from their house and investigates. This is when the teenagers announce their presence and attack Oliver with the car. Unable to stop the teenagers from driving away with their car, Oliver and Clementine retreat inside, where the other teenagers are waiting for them. What follows is an intricate game of cat and mouse throughout the house. The use of documentary-style lighting and camera techniques means that we, like Oliver and Clementine, never know where the teenagers are within the house or, in some instances, in the room. Mounting the camera on the shoulder allows Moreau and Palud to move around the characters as they search the shadows for the intruders. This movement allows them to play with shadows and move actors in and out of the darkness without cutting. This is used to incredible effect during a sequence where Clementine is looking for a way out through the extension they are building at the side of the house.

After being trapped in their bedroom by the teenagers, who have left Lucas too wounded to get past them, Clementine escapes through an attic space to their extension in a bid to get away and summon help. The extension is filled with plastic sheets, both on the floor and hanging from the walls. The only light is the natural light of the moon. As we move through the sheets of translucent plastic, unable to make out what’s behind them, we hear the clacker in the room with Clementine but have no idea where it’s coming from. The camera circles her, showing us every corner of the room to be empty. As the camera swoops back to its starting point we see one of the teenagers step into a carefully placed shaft of light, revealing he was there all along.

Another fantastic sequence, possibly the most famous one in the film, shows us a keyhole view shot of the corridor. The sound of footsteps running up the stairs grows more intense as the camera refuses to move. We cut just once to a close-up of Clementine’s eye as she peers through the keyhole. When we return to the keyhole we see one of the teenagers racing towards the door, right at the last we cut back to Clementine as she reels back from the keyhole, narrowly avoiding having her eye impaled on a screwdriver. It’s a brilliant moment, and the original marketing campaign pushed it to the forefront including having the close-up of Clementine’s eye on the cover art for the home release.

Unfortunately, maintaining such a level of tension as Ils does whilst keeping the film moving forward is a tough task for any filmmaker. Ils does run out of steam as it moves into its third act. Maintaining tension whilst inside the house is straightforward, the claustrophobic setting does a lot of the heavy lifting. Once the film moves outside to the forest surrounding the house, the tension drops off quite quickly. There is some tension building, as I mentioned earlier the clacker is used to form almost a dialogue between the teenagers as they hunt Clementine and Lucas through the forest, but the more open setting with more places to run and hide removes a lot of it. Fortunately, Moreau and Palud recognise this, and once the film moves outside they move fast to wrap it all up.

I avoided Ils upon its first release back in 2006 because it was sold as being part of the New French extremity. I have little interest in watching films that I feel glorify cruelty and torture, despite my interest in the video nasties scare of the 1980s. The marketing focused heavily on the keyhole/screwdriver scene and the brief moments of torture towards the end of the film. I finally got to see Ils back in 2019 because the film wasn’t successful enough to warrant a wide release. I caught it late one night on the Horror Channel in the UK and couldn’t believe I’d avoided it for so long. I’ve been an ardent fan ever since and have sung the film’s praises ever since. If you’re looking for a tense, home invasion thriller and don’t mind subtitles, I recommend Ils.

*New French Extremity films continue to this day. Julia Ducornau’s Raw (2016), Titane (2021), and Gaspar Noe’s Climax (2018) are continuing to push the genre in new and interesting directions.

**It’s worth noting that whilst commonly referred to as the new French extremity, this rise of ultra-violent and extreme cinema was not exclusive to French film and was also popular in Asia, (with Tartan Film creating its own Asia Extreme label of home releases) and Eastern European countries as they began to explore the fall of the Soviet Union through their cinema. If extreme cinema is of interest to you, films from these countries are well worth checking out.

References:

Quandt, J: Flesh & Blood: Sex and Violence in Recent French Cinema. https://www.artforum.com/features/flesh-blood-sex-and-violence-in-recent-french-cinema-168041/

International Labour Organisation: Romanian Street Children. https://www.ilo.org/resource/romanian-street-children

![Them [Ils] - reviews - onderhond.com Them [Ils] - reviews - onderhond.com](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!x0fK!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5ed195b5-dc9b-4123-bf74-813602f15705_1200x400.webp)